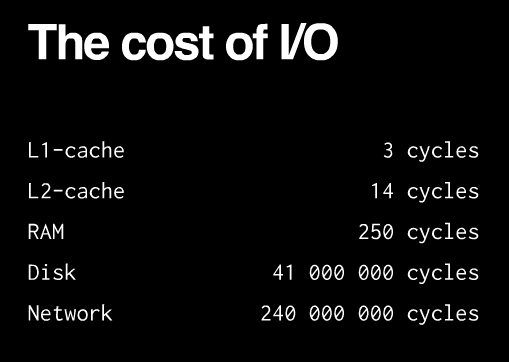

The first basic thesis of node.js is that I/O is expensive:

So the largest waste with current programming technologies comes from waiting for I/O to complete. There are several ways in which one can deal with the performance impact (from Sam Rushing):

- synchronous: you handle one request at a time, each in turn. pros: simple cons: any one request can hold up all the other requests

- fork a new process: you start a new process to handle each request. pros: easycons: does not scale well, hundreds of connections means hundreds of processes. fork() is the Unix programmer’s hammer. Because it’s available, every problem looks like a nail. It’s usually overkill

- threads: start a new thread to handle each request. pros: easy, and kinder to the kernel than using fork, since threads usually have much less overhead cons: your machine may not have threads, and threaded programming can get very complicated very fast, with worries about controlling access to shared resources.

The second basis thesis is that thread-per-connection is memory-expensive: [e.g. that graph everyone showns about Apache sucking up memory compared to Nginx]

Apache is multithreaded: it spawns a thread per request (or process, it depends on the conf). You can see how that overhead eats up memory as the number of concurrent connections increases and more threads are needed to serve multiple simulataneous clients. Nginx and Node.js are not multithreaded, because threads and processes carry a heavy memory cost. They are single-threaded, but event-based. This eliminates the overhead created by thousands of threads/processes by handling many connections in a single thread.

Node.js keeps a single thread for your code…

It really is a single thread running: you can’t do any parallel code execution; doing a “sleep” for example will block the server for one second:

while(new Date().getTime() < now + 1000) {

// do nothing

}

So while that code is running, node.js will not respond to any other requests from clients, since it only has one thread for executing your code. Or if you would have some CPU -intensive code, say, for resizing images, that would still block all other requests.

…however, everything runs in parallel except your code

There is no way of making code run in parallel within a single request. However, all I/O is evented and asynchronous, so the following won’t block the server:

c.query(

'SELECT SLEEP(20);',

function (err, results, fields) {

if (err) {

throw err;

}

res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/html'});

res.end('<html><head><title>Hello</title></head><body><h1>Return from async DB query</h1></body></html>');

c.end();

}

);

Why is this good? When do we go from sync to async/parallel execution?

Having synchronous execution is good, because it simplifies writing code (compared to threads, where concurrency issues have a tendency to result in WTFs).

In node.js, you aren’t supposed to worry about what happens in the backend: just use callbacks when you are doing I/O; and you are guaranteed that your code is never interrupted and that doing I/O will not block other requests without having to incur the costs of thread/process per request (e.g. memory overhead in Apache).

Having asynchronous I/O is good, because I/O is more expensive than most code and we should be doing something better than just waiting for I/O.

An event loop is “an entity that handles and processes external events and converts them into callback invocations”. So I/O calls are the points at which Node.js can switch from one request to another. At an I/O call, your code saves the callback and returns control to the node.js runtime environment. The callback will be called later when the data actually is available.

Of course, on the backend, there are threads and processes for DB access and process execution. However, these are not explicitly exposed to your code, so you can’t worry about them other than by knowing that I/O interactions e.g. with the database, or with other processes will be asynchronous from the perspective of each request since the results from those threads are returned via the event loop to your code. Compared to the Apache model, there are a lot less threads and thread overhead, since threads aren’t needed for each connection; just when you absolutely positively must have something else running in parallel and even then the management is handled by Node.js.

Other than I/O calls, Node.js expects that all requests return quickly; e.g. CPU-intensive work should be split off to another process with which you can interact as with events, or by using an abstraction like WebWorkers. This (obviously) means that you can’t parallelize your code without another thread in the background with which you interact via events. Basically, all objects which emit events (e.g. are instances of EventEmitter) support asynchronous evented interaction and you can interact with blocking code in this manner e.g. using files, sockets or child processes all of which are EventEmitters in Node.js. Multicore can be done using this approach; see also: node-http-proxy.

Internal implementation

Internally, node.js relies on libev to provide the event loop, which is supplemented bylibeio which uses pooled threads to provide asynchronous I/O. To learn even more, have a look at the libev documentation.

So how do we do async in Node.js?

Tim Caswell describes the patterns in his excellent presentation:

- First-class functions. E.g. we pass around functions as data, shuffle them around and execute them when needed.

- Function composition. Also known as having anonymous functions or closures that are executed after something happens in the evented I/O.

- Callback counters. For evented callbacks, you cannot guarantee that I/O events are generated in any particular order. So if you need multiple queries to complete, usually you just keep count of any parallel I/O operations, and check that all the necessary operations have completed when you absolutely must wait for the result; e.g by counting the number of returned DB queries in the event callback and only going further when you have all the data. The queries will run in parallel provided that the I/O library supports this (e.g. via connection pooling).

- Event loops. As mentioned earlier, you can wrap blocking code into an evented abstraction e.g. by running a child process and returning data as it it is processed.

It really is that simple!

相关推荐

Chapter 2, Node.js Essential Patterns, introduces the first steps towards asynchronous coding and design patterns with Node.js discussing and comparing callbacks and the event emitter (observer ...

Beginning Node.js is your step-by-step guide to learning all the aspects of creating maintainable Node.js applications. You will see how Node.js is focused on creating high-performing, highly-scalable...

This short guide will help you develop applications using JavaScript and Node.js, leverage your existing programming skills from .NET or Java, and make the most of these other platforms through ...

The book is meant for developers and software architects with a basic working knowledge of JavaScript who are interested in acquiring a deeper understanding of how to design and develop enterprise-...

This short guide will help you develop applications using JavaScript and Node.js, leverage your existing programming skills from .NET or Java, and make the most of these other platforms through ...

Pro REST API Development with Node.js is your guide to managing and understanding the full capabilities of successful REST development. API design is a hot topic in the programming world, but not many...

JavaScript Applications with Node.js, React, React Native and MongoDB: Design, code, test, deploy and manage in Amazon AWS By 作者: Eric Bush ISBN-10 书号: 0997196661 ISBN-13 书号: 9780997196665 出版...

For this book, you should know HTML and CSS, and you should have a basic understanding of JavaScript. You should also a basic understanding of programming fundamentals, so things like variables, ...

Understanding.the.Linux.Kernel.rar Understanding.the.Linux.Kernel.rar Understanding.the.Linux.Kernel.rar

Understanding the event loop 41 Four sources of truth 42 Callbacks and errors 44 Conventions 45 Know your errors 45 Building pyramids 47 Considerations 48 Listening for file changes 49 Summary 53 ...

Step-by-step development of projects using Ionic Framework as the frontend and Node.js for the backend supported by a MongoDB database Who This Book Is For This book is intended for web developers of ...

Understanding.Network.Hacks.Attack.and.Defense.with.Python Author:Ballmann, Bastian 黑客经典书籍,聚焦于网络七层模型的编程和安全问题。

You’ll learn what makes Node interesting and get a glimpse into the authors’ combined understanding, so that the future directions the Node project takes will make sense. Most importantly, the ...

**Node.js API.ai Recognizer与Microsoft Bot Framework的LUIS.ai** 在开发聊天机器人时,理解和解析用户的自然语言输入是至关重要的。在这个过程中,API.ai(现称为Dialogflow,由Google提供)和Microsoft的LUIS...

本书《SIP - Understanding the Session Initiation Protocol, 2nd Ed》由Alan B. Johnston编写,详细介绍了SIP协议的工作原理和技术细节。 #### 二、SIP协议的历史与发展 - **历史背景**:SIP协议由Mark Handley在...

【标题】"Understanding the SIP 2nd 2004" 涉及的主要知识点是Session Initiation Protocol(SIP)的深入理解,这是一份2004年出版的关于SIP协议的第二版教程。 SIP,即会话初始化协议,是一种应用层控制协议,...